Language Culture / CIVILIZATION

Aperçu des sections

-

WHO IS YOUR TEACHER?

Dr. Amel RAHMOUNI

RANK : MCB

EMAIL: amel.rahmouni@univ-tlemcen.dz

Alternative email: amelrahmouni89@gmail.com

Office times: you can meet and talk to your teacher on Sundays at 09:00 at the teachers' room, or by appointmentWHAT IS ASCC?

ACADEMIC YEAR

2023/2024

MODULE

ANGLO SAXON CULTURE AND CIVILIZATION

INSTRUCTOR

DR. AMEL RAHMOUNI

PERIOD DEDICATED TO LECTURES

· 14 WEEKS

· 22H30

· G01 AND G02 Sunday 10:00 to 11:30

· G07 AND G08 Sunday 11:30 to 13:00

CREDIT

02

COEFFICIENT

01

UNIT

FUNDAMENTAL

EVALUATION

40% Continuous evaluation

60% Final exam

TEACHING METHOD

ONSITE

COURSE DESCRIPTIONTHIS course is dedicated mainly to LMD2 students of English for the purpose of obtaining the necessary knowledge about both British and American culture (s) and civilization (s). The first semester embraces 5 lectures that introduce students to the cultural, political, as well as the social dimensions of Great Britain. It starts with the Age of Enlightenment and ends with the British Imperialism in India. On the other hand, the second semester will be dedicated to America civilization and culture, starting with the American Revolution and its main causes and events and ending with the period of creating and developing the American government with all its branches and structure.

Intended Learning Outcomes: UPON the completion of this course,

students will be able to:

UPON the completion of this course,

students will be able to:- Have a genuine knowledge of the evolution and development of Great Britain and America

- Link the events that took place in Britain and other contemporary events in America

- Understand the chronological order and causality of events that led to the creation of Britain and America in their contemporary images.

- Obtain the necessary knowledge about British power and the effect of Britain’s Imperial power on other parts of the world.

Necessary prerequisites: Students should bring their own texts as well as all the materials sent by the instructor to assure the better engagement and harmony in class.

Course Policies:

-

Participation and students’ involvement are crucial to the success of the

course.

-

Participation and students’ involvement are crucial to the success of the

course. -All students are expected to have read the assigned materials before coming to class in order to play an active role in class and enrich the discussion during each lecture.

- No student is allowed to inter to the classroom after the door is closed? or after 15 minutes of lecture's beginning.

-Absences should be justified. Students with 3 unjustified absences, or 5 justified absences are to be excluded.

- No make-up exams: in case of sickness, only reports issued and stamped from the University’s clinic will be accepted.

-Plagiarism is a serious academic offense that will result in your failure in class.

Course Program:

Semester 1:

- The Age of Enlightenment (The Age of Reason)

- The Industrial Revolution

- The Chartist Movement

- The Victorian Era

- British Imperialism in India

Semester 2:

- The American Revolution

- Westward Expansion

- The American Civil War

- The Reconstruction Era

- The American Government

Bibliography and Suggested Resources:

Aziz, Khursheed Kamal. British Imperialism in India. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, 1989.

Berlin, Isaiah. The Age of Enlightenment. Oxford University Press, 1979.

Black, Joseph Laurence. The Victorian Era. Broadview Press, 2013.

Churchill, Winston, and Winston S. Churchill. The Great Republic: A History of America. Random House, 1999.

King, Steven, and Geoffrey Timmins. Making Sense of the Industrial Revolution: English Economy and Society 1700-1850. Manchester Univ. Press, 2004.

Quay, Sara E. Westward Expansion. Greenwood Press, 2002.

Sakolsky, Josh. Critical Perspectives on the Industrial Revolution. Rosen Pub. Group, 2005.

Simonelli, David. “Chartism in Great Britain.” African American Studies Center, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.44617.

Wells, Peter. The American War of Independence. Holmes & Meier, 1978.

-

This spcae is created to assure communication between students and the teacher. whenever you have any questions, you can use this forum.

This spcae is created to assure communication between students and the teacher. whenever you have any questions, you can use this forum.

-

-

What was the Age of Enlightenment?

Immanuel Kant argues that “the motto of enlightenment is therefore: Sapere aude! [Dare to be wise] Have courage to use your own understanding!”

-

Enlightenment Defined

The Enlightenment, also known as The Age of Reason,

was a philosophical and cultural movement that dominated the world of ideas in

Western Europe during the 18th century. In the simplest words

possible, states that the Enlightenment was “born of the idea that all human

beings share the same basic needs and as such should enjoy the same rights and

privileges” (Hourly History, 21). Enlightenment philosophers believed that

human reason, rationality, and benevolence would lead to the natural

progression of society and the betterment of life on Earth. The preceding

scientific revolution that took place in Europe convinced many European

thinkers that reason is the most powerful tool that human beings can use to

achieve truth, study human nature, and solve all human problems. Philosophers

of the Enlightenment started to convince people that truth could only be

achieved through Empirical investigation and deductive reasoning.

The Enlightenment, also known as The Age of Reason,

was a philosophical and cultural movement that dominated the world of ideas in

Western Europe during the 18th century. In the simplest words

possible, states that the Enlightenment was “born of the idea that all human

beings share the same basic needs and as such should enjoy the same rights and

privileges” (Hourly History, 21). Enlightenment philosophers believed that

human reason, rationality, and benevolence would lead to the natural

progression of society and the betterment of life on Earth. The preceding

scientific revolution that took place in Europe convinced many European

thinkers that reason is the most powerful tool that human beings can use to

achieve truth, study human nature, and solve all human problems. Philosophers

of the Enlightenment started to convince people that truth could only be

achieved through Empirical investigation and deductive reasoning. Little consensus is available concerning specific dates of the movement. Most historians agree that the Enlightenment began around the 1680s and lasted until the early 1800s. Some historians and philosophers have argued that the beginning of the Enlightenment is when Descartes shifted the epistemological basis from external authority to internal certainty by his cogito ergo sum “I think, therefore I am” (1637). Francis Bacon is another thinker and the founder of the empiricist strain that conceived the new sciences as based mainly on empirical observation and experimentation and whose ideas paved the way for the major thoughts of the Enlightenment. As for its end, the French Revolution (1789) is mostly chosen to date the end of the Enlightenment era. However, historians have also listed numerous historical movements as wellsprings of enlightened thought. These mostly include:

· Renaissance: For some, the Enlightenment was the direct result of the Renaissance and the Reformation as the “Cultural rebirth” of Europe. Renaissance era encouraged the revival of classical art, literature, and even architecture.

Reformation: It shook the authority of the Church in Europe to its core as the Protestants rebelled against Catholic Church, putting individual conscience ahead of authority of the Church

Scientific Revolution: Scientists discovered new truths about natural life by using experimentation, logic, reason, and observation. Newton’s influence was the strongest single factor. Isaiah Berlin notes that “Newton had performed the unprecedented task of explaining the material world…to determine the properties and behavior of every particle of every material body in the universe” (Berlin, 5). As a result, thinkers started to conclude that reason and logic could also be used in understanding the human mind, human relations, social, religious, and political life.

Major Enlightenment Thinkers

Jean Jacque Rousseau: in his

writings, especially The Social Contract, he challenged the long living

idea that the

king has a God-given right to rule his people. He also questioned the

King’s absolute power. Rousseau argued that democracy was the best form

of government. It would defend individual rights and assure prosperity

for all people. Rousseau also asserted that People should choose how to

be ruled. He opposed absolute monarchs and titles of nobility because

of his belief that all people are born equal.

Jean Jacque Rousseau: in his

writings, especially The Social Contract, he challenged the long living

idea that the

king has a God-given right to rule his people. He also questioned the

King’s absolute power. Rousseau argued that democracy was the best form

of government. It would defend individual rights and assure prosperity

for all people. Rousseau also asserted that People should choose how to

be ruled. He opposed absolute monarchs and titles of nobility because

of his belief that all people are born equal.

Rousseau claimed that advocates of the Enlightenment relied too much on reason. Instead, people should pay more attention to their feelings. According to Rousseau, human beings were naturally good, but civilized life corrupted them. To improve themselves, he thought people should live simpler lives closer to nature.

John Lock: He did not oppose monarchies, but disagreed

with the divine right of kings and argued that the power of the

government came from people who gave their consent to be governed.

Hence, the government was bound to protect what Lock terms as people’s “natural

rights”. He argued that people had the right to revolt if the

government fails in protecting these rights of life, liberty, and

property.

John Lock: He did not oppose monarchies, but disagreed

with the divine right of kings and argued that the power of the

government came from people who gave their consent to be governed.

Hence, the government was bound to protect what Lock terms as people’s “natural

rights”. He argued that people had the right to revolt if the

government fails in protecting these rights of life, liberty, and

property.  Voltaire: Born Froncois

Marie Arouet: Voltaire wrote against superstition in church and against religious

intolerance. Despite being jailed many times and being exiled out of

France, he kept spreading his ideas and insisting on freedom of speech. He strongly insisted on the idea that every

person has the right to liberty. His famous quote is “I

disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say

it.

Voltaire: Born Froncois

Marie Arouet: Voltaire wrote against superstition in church and against religious

intolerance. Despite being jailed many times and being exiled out of

France, he kept spreading his ideas and insisting on freedom of speech. He strongly insisted on the idea that every

person has the right to liberty. His famous quote is “I

disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say

it.Voltaire became known for his strong dislike of the Roman Catholic Church. He blamed Church leaders for keeping knowledge from people in order to maintain the Church’s power. Voltaire also opposed the government supporting one religion and forbidding others. He thought people should be free to choose their own beliefs. Voltaire, like many philosophes, supported deism.

Baron de Montesquieu. He came up

with the idea of the Separation of Powers to prevent the possibility that

a government will be too powerful. Montesquieu proposed that a government

should be divided into three parts: 1. one that makes laws (legislative).

2. One that enforces them (executive). 3. The third one is the (judiciary)

to interpret these laws. This division of powers assures that each part will

keep the others in check. He published a

book entitled the Spirit of Laws.

Baron de Montesquieu. He came up

with the idea of the Separation of Powers to prevent the possibility that

a government will be too powerful. Montesquieu proposed that a government

should be divided into three parts: 1. one that makes laws (legislative).

2. One that enforces them (executive). 3. The third one is the (judiciary)

to interpret these laws. This division of powers assures that each part will

keep the others in check. He published a

book entitled the Spirit of Laws.Women in the Age of Enlightenment:

Most Enlightenment philosophers supported the equality of men, but not women. Rousseau wrote that “woman was specifically made to please man”. This urged many women to call for their rights as reasoning beings. As an attempt to change this reality, women used reason to argue for equal rights. In France, wealthy and intelligent Women hosted social gatherings called “salons”. Most philosophers of the time were invited and women extracted their ideas and wrote those discussions in newspapers to assure the spread of “equality ideas” among all social groups.

In addition to that, women showed real thirst for education. In 1792 Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman where she argued that well educated women will serve society by bringing up enlightened generations. As a result, eighteenth-century writers increasingly came to believe that “the status and educational level of women in a given society were important indicators of its degree of historical progress, and a number argued that the low educational level of women in their own times was itself an impediment to further social improvement” (O’Brien 2).

Natural Rights of Women Mary Wollstonecraft argued that the natural rights of the Enlightenment should extend to women as well as men. “In short, in whatever light I view the subject, reason and experience convince me that the only method of leading women to fulfill their peculiar [specific] duties is to free them from all restraint by allowing them to participate in the inherent rights of mankind. Make them free, and they will quickly become wise and virtuous, as men become more so, for the improvement must be mutual.” —Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects.

Impact of the Age of Reason

The Age of the Enlightenment paved the way to numerous historical events such as The French Revolution, Religious tolerance, the creation of modern, liberal democracies, and the spread of equality among further social and ethnic groups (women, people of color, working masses). In America, Enlightenment ideas were brought and applied by figures such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson and used in historical documents such as The U.S Bill of Rights and the American Declaration of Independence.

-

-

-

BRITAIN BEFORE 1750

Before 1750, most people lived in small villages. They travelled on foot or by horses through small paths. Illness was common because of inadequate food, poor hygiene, use of polluted water, and non-existence of sewage system. As a result, life expectancy was very short. About 80% people worked in small agricultural farms in rural areas and the rest 20% lived in small towns. The villagers worked from sunrise to sunset (Oxford Geography, 269). Very few people worked in manufacturing, mining and trade units. Manufacturing was small and localized. People used handmade tools powered by people or animals. About 1% citizens were aristocratic families by birth. However, this small group of people controlled about 15 per cent of Britain’s wealth. They did not work; instead, they only invested much of their wealth in land (Clark, 2010; Jacob, 1997).

Factors that Paved the Path to the IR

The Agricultural Revolution: It

could be safely said that the Agricultural Revolution was the basic step that

led to the flourishing of the IR. The changes in the methods of farming and

stock breeding that characterized this agricultural transformation led to a

significant increase in food production. British agriculture could now feed

more people at lower prices with less labor. Unlike the rest of Europe, even

ordinary British families did not have to use most of their income to buy food,

giving them the potential to purchase manufactured goods.

The Agricultural Revolution: It

could be safely said that the Agricultural Revolution was the basic step that

led to the flourishing of the IR. The changes in the methods of farming and

stock breeding that characterized this agricultural transformation led to a

significant increase in food production. British agriculture could now feed

more people at lower prices with less labor. Unlike the rest of Europe, even

ordinary British families did not have to use most of their income to buy food,

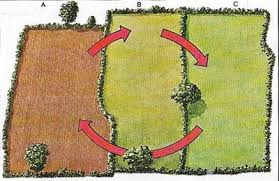

giving them the potential to purchase manufactured goods. The enclosures and crop rotation: More

than 4000 Enclosure Acts were passed by the British Parliament during

the Agricultural Revolution. Wealthy landowners had bought their lands from the

village farmers and enclosed their land with fences. They also cultivated the

larger fields. Wealthy landowners forced small farmers to become tenant farmers

or to give up farming and move to the cities to work industries. The crop

rotation and farm machinery were two other factors that improved agriculture

and urged former farmers to leave to new cities.

The enclosures and crop rotation: More

than 4000 Enclosure Acts were passed by the British Parliament during

the Agricultural Revolution. Wealthy landowners had bought their lands from the

village farmers and enclosed their land with fences. They also cultivated the

larger fields. Wealthy landowners forced small farmers to become tenant farmers

or to give up farming and move to the cities to work industries. The crop

rotation and farm machinery were two other factors that improved agriculture

and urged former farmers to leave to new cities. Britain’s coal supplies: Britain was richly supplied with important mineral resources, such as coal and iron ore, needed in the manufacturing process.

The Capitalist spirit and individual freedom: Parliament passed laws that protected private property and enterprise. Britain was a fertile ground for people willing to try new things and take risks. The absence of political and social conflict also was a factor that encouraged the growth of business (Clark et al., 2008).

Superior banking system and capital for investment: Britain had a ready supply of capital (money) for investment in

the new industrial machines and the factories that were needed to house them.

In addition to profits from trade and cottage industry, Britain possessed an

effective central bank and well-developed, flexible credit facilities. Supply

of capital at low interests enabled the new businesses to start up. There was

also enough money to pay for experiments to develop new inventions (Deane and

Cole, 1962).

Superior banking system and capital for investment: Britain had a ready supply of capital (money) for investment in

the new industrial machines and the factories that were needed to house them.

In addition to profits from trade and cottage industry, Britain possessed an

effective central bank and well-developed, flexible credit facilities. Supply

of capital at low interests enabled the new businesses to start up. There was

also enough money to pay for experiments to develop new inventions (Deane and

Cole, 1962). Naval and trading powers: Britain was an island nation that relied on skilled sailors as well as a strong navy and well experienced fleets of merchant ships. Its largest merchant trading company was the East India Company (EIC) that rivaled many smaller European powers in wealth and influence.

TRAITS OF THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: the Industrial Revolution was characterized by many changes and inventions in almost all aspects of life. Some examples are as follow:

- Textile Industry: John Kay (1704–1779) invented and developed the flying shuttle in 1747 (Hawke, 1993; Simkin, 2003). James Hargreaves (1720–1778) patented spinning jenny in 1770. Sir Richard Arkwright (1732–1792) invented the water frame in 1769 which used the waterpower from rapid streams to drive spinning wheels (Gernhard, 2003; Szostak, 1991). Weavers were no longer needed as Britain imported its cotton from America to manufacture it. As a result, Britain became the world’s dominant power of textile industry.

- Iron Industry: A better quality of iron was not possible until the 1780s when Henry Cort developed a system called puddling, in which coke was used to burn away impurities in pig iron to produce an iron of high quality. A boom then ensued in the British iron industry. In 1740, Britain produced 17,000 tons of iron; in the 1780s, almost 70,000 tons; by the 1840s, over two million tons; and by 1852, almost three million tons, more than the rest of the world combined.

- The steam engine: One of the great technological advances came in 1712, with the invention of a steam engine by an English blacksmith, Thomas Newcomen (1664–1729). His invention is considered as the “atmospheric engine” (Sinclair, 1907). This engine burned coal to create motive force that could be used to pump water out of the shafts of coal mines. Scottish mechanical engineer James Watt (1736–1819), working in a Glaswegian university lab of England, improved Newcomen’s steam engine in 1776, which harnessed massive amounts of coal-powered energy efficiently and economically (Jacob, 1997; Usher, 1920).

- Improvement of transportation: James Watt’s steam engine was used in water transportation to propel boats and steamships. In England, canals and other human-made waterways were used to transport raw materials and finished goods. In 1804, Richard Trevithick (1771–1833), an English engineer, transported ten tons of iron and 70 men over nearly ten miles of track in a steam-driven locomotive. It is the first locomotive built to run on rails (Sinclair, 1907). In 1821, George Stephenson (1781– 1848), an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer, built some 20 engines for mine operators in northern England. In 1829, the railroad opened under the supervision of Stephenson whose engines can move 29 miles per hour which was called “Rocket”.

- The Great Exhibition: In 1851, the British organized the world’s first industrial fair. It was housed at Kensington in London in the Crystal Palace, an enormous structure made entirely of glass and iron, a tribute to British engineering skills. Covering nineteen acres, the Crystal Palace contained 100,000 exhibits that showed the wide variety of products created by the Industrial Revolution. Six million people visited the fair in six months.

The Impact of the Industrial Revolution

the IR brought numerous advantages to Britain. Nonetheless, it also had a darker facet that affected the British society negatively.

The growth of cities and population: Cities were rapidly becoming places for manufacturing and industry. With the steam engine, entrepreneurs could locate their manufacturing plants in urban centers where they had ready access to transportation facilities and unemployed people from the country looking for work. During the IR child and infant mortality rate decreased and fertility rate increased due to the development of medical science, improvement of sanitary system and economic development (Murmann, 2003). In 1800, Great Britain had one major city, London, with a population of 1 million, and six cities between 50,000 and 100,000.

Pollution: The coal that powered factories and warmed houses polluted the air dangerously. Textile dyes and other wastes poisoned river water. Industrialization and rapid urban growth produced dreadful living conditions in many nineteenth-century cities. Filled with garbage and human waste, cities often smelled terrible and were extremely unhealthy.

New Social classes: As the income of the workers was very low, they lived in dark, dirty shelters, with whole families crowding into one bedroom. They found little improvement in their living and working conditions (Flinn, 1966). Accidents and illness were very frequent. On the other hand, factory owners, merchants, and bankers grew wealthier than the landowners and aristocrats. A larger middle class, such as government employees, doctors, lawyers, and managers of factories, mines, and shops had grown. They enjoyed a comfortable standard of living (Rostow, 1960).

Child and Women labour: children were seen as ideal employees. They were small enough to fit between the new machinery, they were cheap to employ and their families were grateful for the extra income. Education was not a big concern as it was not compulsory. Children often started work at the age of four or five in jobs that were physically demanding. To keep the children awake, mill supervisors beat them. They found half an hour for lunch and an hour for dinner (Galbi,1994). Many children developed lung cancer, tuberculosis, cholera, and other diseases and died before the age of 25. Many died from gas explosions or crushed under the machines or burned. Some lost limbs or blinded (Rosen, 2012). Women were also an easy target as they worked for lower wages than men and did not have the power or right to negotiate their rights due to their need for sustenance.

-

-

WHAT WAS CHARTISM ABOUT?

In very basic terms Chartism may be defined as “a working-class movement to obtain representation in Parliament” (Taylor, 386).

-

What Was Chartism?

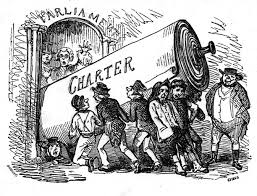

In very basic terms Chartism may be defined as “a working-class movement to obtain representation in Parliament” (Taylor, 386). Micheline Ishay states that Chartism was an attempt towards parliamentary reforms and that it focused on winning working-class representation in parliament, universal suffrage for all adult males, and the reduction of working hours” (332). It aimed at assuring further economic and social reforms. Chartism was, in the words of Joseph Rayner Stephens, a Chartist agitator in the North of England, 'a knife and fork question, a bread and cheese question' (qtd.in. Jones, 1975, 121); meaning that political power was only the means to achieving better living conditions for the working people and not merely an end in itself.

The Charter was the work of William Lovett, Henry Hetherington and, to a lesser degree, Francis Place. All three were members of the London Working Men's Association (LWMA) a group of skilled craftsmen who recognized the need to gain political representation for the working classes (Taylor, 386). These were mainly “working class activists who supported the drive to persuade Parliament to adopt the ‘People’s Charter’” (Morgan, 89). After discussing the issues with Thomas Attwood's Political Union in Birmingham, the six demands were made public in May 1838. The People's Charter had six main aims: universal manhood suffrage (all men over 21 to have a vote), the payment of MPs, the abolition of property qualifications rule for men wishing to stand for parliament, the holding of secret ballots at general elections, annual Parliament elections, and equal electoral districts (voting districts which were the same size).

WHAT WERE THE FACTORS THAT ENCOURAGED THE MOVEMENT?

The following factors were the most important in encouraging people to support the Chartist movement:

- Disappointment with the 1832 Reform Act: The working class had combined with the middle class and taken part in demonstrations for reform, but did not obtain the vote in this Act (Beechener, Griffiths, and Jacob, 50). Only an estimation of 700000 people of the middle class were given this privilege. Working classes then searched for a new way to get their demands.

- The 1833 Factory Act was another disappointment: it failed to achieve the goal of reducing the working hours to 10 hours per day (Taylor, 387).

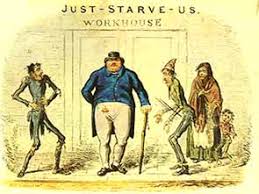

- Bitterness towards the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act: Richard Oastler believed that the government had ‘made poverty a crime’. The situation was made worse as the decision to accelerate the building of new union workhouses (bastilles) coincided with a trade depression and high unemployment at the end of the 1830s (Taylor, 387).

- The suppression of trade unionism: Although trade unions could exist, their powers to hold a successful strike were in doubt. The government introduced measures to prevent collective action on the part of workers.

- Fluctuations in trade: The years of 1838-9, 1842, and 1847-8 were ones of trade recession and high unemployment, with thousands of working families in poverty and despair. In the words of Halevy, Chartism ' was not a creed. It was the blind revolt” (Halévy, 323) of hunger'. People also suffered from high taxation and high food prices when harvests were bad.

THE MAIN EVENTS OF THE CHARTIST MOVEMENT

The First National Petition of 1939:

This petition was the first act taken by the Chartists to seek political change. Lovett, Attwood, and O’Conner decided that a petition should be represented to Parliament with as many signatures as possible (Taylor, 392). The Petition was presented to Parliament by Thomas Attwood on June. It was almost three miles long and contained 1, 280,000 signatures of both genders. However, since Parliament was still dominated by the landowners who had deep fear of losing their privileged positions, the petition was rejected by 235 votes to 46 (Wagner, 3-4). This refusal made the Chartists very furious, going on numerous riots around the country including the Bull Ring Riots in Birmingham. A number of delegates favoured a General Strike (or Sacred Month) accompanied by a period of civil disobedience where the Chartists would not pay taxes.

The Newport rising:

The idea of the 'Sacred Month' did not materialize and the National Convention was dissolved in September while local groups started to take their own steps. Violence broke as the ‘Rising’ was the most serious manifestation of ‘physical force Chartism’. The Westgate battle was the bloodiest and 24 Chartists were killed by troops. Many leaders such as Henry Vincent were arrested. The aftermath of the Newport Rising was the further arrest of leading Chartists, including O'Connor and O'Brien (Taylor, 393).

The second Chartist petition 1842:

Between 1840 and 1842 Chartist activity was not so intense Trade had improved and more people were in employment. In autumn 1841 the Chartist leaders had been released and they each tried to reassert their authority on the movement. The result was public disagreement and bickering. With trade declining in spring 1842 there was once again a resurgence in interest in Chartism. A second petition was prepared, this time with 3 315 752 signatures. It was presented to Parliament by Mr T. Dancombe, who pointed out the gross inconsistencies in the electoral system. This time the petition was rejected by 287 votes to 49.

The plug riots August 1842:

widespread rioting and strikes broke out in Yorkshire, Lancashire, Scotland, the West Midlands and South Wales. In many towns factories were brought to a standstill as mobs removed the plugs from the steam-engine boilers. At Bury 33 mills were idle. Eventually order was restored by troops and offenders were punished by the court. Lovett broke with the movement, leaving O'Connor as the main personality.

O'Connor and land reform:

O'Connor, assisted by Ernest Jones, founded 'The National Land Company'. The idea was to collect money from sympathizers and buy units of land that could be divided up into small plots and rented out. For a time the Land Scheme looked like being successful. Five estates were bought. In the end the scheme collapsed as many families could not afford the rent and moved away. The Parliament once more attempted to stop this process, claiming that O’Conner embezzled the funds.

The third national petition 1848:

In April 1848 a third and final petition was presented. A mass meeting of 20000 people gathered on Kennington Common in South London under the leadership of Chartist leaders, the most influential being Feargus O'Connor, editor of 'The Northern Star'. However, O’Conner told the crowds that he will personally present the petition that contained 5700000 signatures to Parliament since the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Mayne, told O’Conner that the crowd that a procession would not be allowed over Blackfriar’s Bridge to Westminister (Taylor, 395). Eventually, a special committee claimed that only 1975496 signatures were genuine and that numerous names were fictitious such as “No Cheese” and “Big Nose”. The petition was rejected amidst great hilarity by 222 votes to 17. This time anticipated unrest did not happen. Despite the Chartist leaders' attempts to keep the movement alive, within a few years it was no longer a driving force for reform.

WHAT ARE THE FACOTRS THAT LED TO THE FAILURE OF CHARTISM?

Inherent weakness within the movement:

Chartism composed of many local organizations that had different aspirations. It was difficult to unite the interests of such groups that included craftsmen, factory-operatives, and domestic workers. Moreover, poor communications and “lack of funds made the problem worse” (Taylor, 396).

Poor leadership:

the movement was divided into two groups that were at odds with each other:

· Physical Force: physical force tactics were most prominent in the north that witnessed the worst working conditions. William Lovett preferred “peaceful evolution” and then disassociated himself from the movement in 1842 when it started to take a violent path. Henry Hetherington and Thomas Attwood were also advocators of moral force.

· Moral Force: the method was preferred by Scottish Chartists where working conditions were less dangerous. Some historians also suggest that moral force Chartism happened because workers were not subject to the New Poor Law. Feargus O’Connor and James Bronterre O’Brien are believed to be “ardent” believers in physical force, despite the opposite claims of O’Conner. The Chartists also disagreed as to how much support they should seek from the middle classes. O'Conner and O'Brien were opposed to any merger with the middle classes, disagreeing with the opinions of Lovett.

Lack of middle-class support:

Once violence started many of the middle classes scorned any association with Chartism. This lost the movement potential funding.

Mid-Victorian Prosperity:

After the 1840s trade improved. Wages were increased, employment was high and people generally lost interest in political movements. Workers rather trusted trade unionism.

Government Tactics:

The government seemed prepared to allow peaceful meetings of the chartists to go ahead. On the other hand, all kinds of violence were immediately met with serious responses. “Heavy punishments were given to the Newport men (1839) and the plug riots in 1842” (Taylor 397).

DID CHARTISM FAIL FOR REAL?

The Chartists' legacy was strong. By the 1850s Members of Parliament accepted that further reform was inevitable. Over the years five out of six of the Chartist’s demands have become law. These include: Abolition of property qualification 1858, secret ballot 1872, equal constituencies 1885, payment of members 1911, and Universal suffrage 1918. Annual parliament election never became a law because of its impracticality and because such a decision would cost the government much while not guaranteeing any continuity in running the country. Historians of the Labour Movement see Chartism as the forerunner of the socialist revival of the 1880s and as such it is important in the 'development of a working class'.

-

-

-

Lecture: The Victorian Era

Introduction

The expression “Victorian Age” or “Victorian Era” refers to the period of time when Britain was under the reign of Queen Victoria. King William IV died on June 20, 1837, leaving no legitimate offspring. As a result, his eighteen-year old niece Victoria (granddaughter of George III) became queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Her reign ended in 1901, being one of the longest reigns in the history of England. This age witnessed the most significant changes in almost every aspect of politics, law, economics, and society.

The Victorian age was first and foremost an age of transition. The England that had once been a feudal and agricultural society was transformed into an industrial democracy. Between 1837, when eighteen-year-old Victoria became queen, and 1901, the year of her death, social and technological change affected almost every feature of daily existence. Many aspects of life-from schooling to competitive sports to the floor-plan of middle-class houses to widely held ideals about family life- took the shape that has been familiar for most of the twentieth century.

Queen Victoria’s Reign

For her political education, Queen Victoria owed much to her adviser and friend William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, who had been Prime Minister since 1835. Victoria was said not to be the real reason why the Victorian Age was so successful in England. Most of the real credit should go to her very able prime ministers Benjamin Disraeli and Lord Melbourne, her father figure. They guided her, along with Prince Albert, in the ways of politics. Victoria had a great impact on Europe as well. She had been called the “Grandmother of Europe”. Two of her grandsons were Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and Czar Nicholas II of Russia. Many of her children and grandchildren married into the other royal families of Europe.

Victoria’s ideals were the ones of most of the British public. Her ideals were very puritan. Being a puritan meant that she believed in strict Christianity and discipline. Many paintings show her with “her nosed turned up” in severity. She heavily believed in discipline.

The Victorian British Empire

Imperialism may be defined as “the sustained effort to assimilate a country or region to the political, economic or cultural system of another power” (Darwin, 614). During the reign of Queen Victoria, Britain achieved dramatic overseas expansion. In 1876, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli sent to Parliament a bill that gave Queen Victoria the title “Empress of India”. New territories were acquired: Burma and Malaysia to safeguard the borders of India; islands and ports and coaling stations to secure continued English dominance over the seas; pieces of China and the Middle East to protect trade routes or gain economic advantages. During the final decades of the century, England competed with other European nations in the “scramble for Africa” that made most of the continent into colonial territory. Noteworthy, during this period Britain did not lose any war due to its strong navy. Some main events from this era are as follow:

The Opium War (1839-1842):

the war had its roots in a trade dispute between Britain and China. The British imported many goods from China in exchange for silver while the Chinese showed no interest in Western products due to their self-sufficient economy. In order to cure the trade deficit, the British blamed China’s closed-door policy and started to smuggle opium to Chinese people, creating huge addiction and succeeding in tipping trade balance. As a reaction, the Chinese wanted to stop opium trade. However, Britain sent its troops to China and started a war that ended with the victory of the British.

The Crimean War (1853-1856):

From 1854 to 1856, England and France were allies in a war against Russia in the Crimea (modern-day Ukraine), which lies between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azof and was then a part of the disintegrating Turkish Empire. The causes of the Crimean War have never been entirely clear, but it was part of a struggle between England and Russia to maintain influence in the Middle East and thereby protect trade routes into Asia. The Alliance won because the Russians could not supply their troops. The Russian railroads became broken and the Russians could not fix them.

The Boer War (1899-1902):

The Boer War (1899-1902) was fought in South Africa between the British colonists and the Dutch colonists (called Boers) living in South Africa. This war is often called the first “total” war because both sides fought endlessly. In the end, the British won and all of South Africa was under British control.

Not stopping this far, the British Empire grew wider and covered wider areas. Victoria was an important proponent in transferring control of India from the East India Company to the British government in 1858. Victoria was declared “Empress of India” in 1876. The British gained control of Egypt (with the Suez Canal) in 1869 and many other areas. The British Empire became the richest country in the world during the reign of Queen Victoria. There were many sayings like, “The sun never sets on the British Empire”, and “The workshop of the world”, that described Britain in the nineteenth century. By the time of the 1897 Diamond Jubilee celebrating the 60th year of Queen Victoria’s rule, her Empire contained one-quarter of the world’s population. Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887 was an outpouring of national affection and a celebration of 50 years of domestic progress. The Great Exhibition showed off the nation’s great industrial triumphs. The Diamond Jubilee of 1897, by contrast, marked the high tide of Empire.

The Woman Issue

Queen Victoria had married her cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, in 1840. Over the next 17 years she gave birth to nine children and became increasingly popular as a moral leader and model of family values. A Victorian journal summed up the role of women in mid-Victorian times in the phrase that “married life is a woman’s profession”. Accordingly, middle class women in households were not expected to have a job. This was one of the things that marked them out as different from the working class. Even if young women had an adequate job they had to resign when they got married. The most conventional image of the perfect Victorian woman is found in the title of a long poem written by Coventry Patmore: The Angel in the House. A woman was supposed to help regenerate society through her daily display of Christianity in action.

Marriage was seen as woman’s natural and expected role: it satisfied her instinctual needs, preserved the species, provided appropriate duties, and protected her from the shocks and dangers of the rude, competitive world. In the late Victorian period teaching had become one of the professions for middle class women, especially, when education for children under ten years old had been made compulsory in 1870. Most working class women did not have a choice whether or not they went to work. Their families simply needed the additional money to survive. What both working class and middle class women had in common was the fact that they had hardly any rights. When for example a young woman married all her possessions became her husband’s property. It was not a crime when a husband hit his wife, and the children were legally the husband’s. A few middle class women dared to campaign for women’s rights, including Annie Besant (d. 1933) and Josephine Butler (d. 1900), who also both fought for birth control and socialism.

One of the most successful campaigns carried out by women was for better education. When school education had been made compulsory for children under 10 all children had to do reading, writing, arithmetic, but some subjects were just for girls. A school syllabus for girls in Bristol in 1899 listed lessons such as ‘how to light a fire’, ‘removing tea stains’, and ‘porridge making’. By 1900 women had won many improvements in their education and also in their legal rights. After 1882 (The Married Women´s Property Act of 1882 and 1892), they were allowed to keep their own income and property after they married, but they were still denied the vote in general elections and barred from holding political office. Political changes did not take place until after the First World War when the 1918 Act allowed women over 30 to vote. Women over 21 had to wait until 1939.

Compulsory Education for children under ten 1880

The elementary education act of 1880 was a policy that made school attendance mandatory from ages five to ten. Introductory by social reformer and member of liberal party A.J. Mundella, the education bill quietly overrode the factory acts, dramatically reducing the amount of time young children were allowed to spend in mill and factory work. However; education opportunities differed from one class to another.

Religion and Science in the Victorian era

The Victorian era was fundamentally a religious age; even more religious than the preceding 18th century. Christian principles and beliefs were seen as the real tool that bounds a society together. The Historian A. Froude asserted that “an established religion is the sanction of moral obligation; it gives authority to the commandments, creates a fear of doing wrong, and a sense of responsibility for doing it”. Alongside faith, science was another main characteristic of Victorian England to the extent that lead many to fear that it would somehow shake religious faith. R.K Webb explained that the number of people whose religious faith was shaken by scientific discoveries was “probably fairly small” but consisted of “people whose opinions counted for much”.

Victorians made and appreciated developments in science. Charles Darwin, the British biologist and naturalist published his famous theory on the origin of species on 24 November, 1859. It presented his theory of evolution by natural selection and adaptation of the species. The book became an international best-seller, but opinion on the argument for evolution and natural selection remained fiercely divided throughout Darwin’s life. Victorians were also fascinated by the emerging discipline of psychology and by the physics of energy.

Growth of economy and new social classes

In the first 50 years of the 19th century Britain had ‘witnessed a leap forward in all the elements of material wellbeing,’ the author of an article in The Economist wrote in 1850. “The extended application of machinery [is] almost putting an end to very severe bodily toil except in agriculture.” Britain’s economic position in that period seemed to support the optimism and confidence of the time and to justify the reference to Britain as ‘the workshop of the world’. From 1820 to 1888 the industrial production rose from £ 230 million to £820 million.

In spite of these figures, it could be safely said that Victorian Britain was “a fine place for the rich, but the Lord help the poor,’ a researcher once noted. Industrial Britain mainly contained three different social classes:

The upper class: the aristocracy and gentry, continued to dominate political and social life. In 1873 the top group of the upper class, i.e. less than 7, 000 people out of a population of 31 million, owned 4/5 of the land in the UK. This class had the biggest political influence and did not have to spend much time to earn an income as they were rich by heritage. They lived part of the year in “country estates” with up to 40 servants or in “town houses” depending on the seasons and weather.

Middle class: The keeping of domestic servants marked the division from working class. At the top of this class (in London) were bankers and city merchants. The lower middle class was formed by shopkeepers and small businessmen, then white-collar workers, such as teachers and clerks. Income in the middle classes was based on non-manual jobs in business or the professions (law, medicine, education, religion, art and entertainment, literature and science).

Working class: 75% of the population. They earned their income from manual work. The working class was formed of labourers, farm hands, factory workers, railway-men, domestic servants and others. Almost all workers were liable to unemployment at some time. They lived in dreadful workhouses and in constant fear of accidents.

Victorian Cultural Blossoming

During the first half of the nineteenth century, reading was hardly a popular pursuit. Much of the population was unschooled, and, more importantly, printed matter was too expensive for the common man. Books were also expensive and were considered luxuries, which is why it was a sign of wealth and prestige for a private home to include a library, the shelves well stocked with leather-bound volumes.

The British made many advances in the academic field. The increasing middle-class people were the class portrayed in the novels and to whom the novels were written. Thus Victorian novelists were inclined to treat the predominance of money with angry satire. We have the arrogant "nouveau rich" merchant such as William Thackeray's Mr Osborne in Vanity Fair (1848) and Charles Dickens´s Podsnap in Our Mutual Friend (1865). Between the rich middle classes and the workers, a very large lower middle class existed; its members populate the novels of Dickens and H.G. Wells more than the members of any other class.

Many places around the world are named after Queen Victoria. Lake Victoria, in Africa and the lake where the Nile River starts, was named for Victoria, along with Victoria Falls named by the Scottish explorer Dr. Livingstone. Victoria, a state in Australia, is also named for the queen.

-

-

How did the British invade India? When and why did that happen?

navigate through the coming lecture to discover all of these details!!!

-

Lecture Five: British Imperialism in India

The East India Company: Trade was the first intention!

The first British in India were traders, not conquerors. In 1600, a group of English merchants secured a royal charter for purposes of trading in the East Indies. Their company, known as The East India Company, turned its attention to the vast expanse of India. (Blackwell, 34. The Age of Imperialism, 357). The Industrial Revolution had turned Britain into the world’s workshop, and India was a major supplier of raw materials for that workshop. Its 300 million people were also a large potential market for British-made goods. About “twenty to thirty ships were sent yearly and were worth up to £2 million” ( Mastoi, Lohar, and Ali Shah, 25). It is due to this reason that the British considered India as the brightest “Jewel in the Crown”. Until the beginning of the 19th century, the company ruled India with little interference from the British government. The company even had its own army, led by British officers and staffed by sepoys, or Indian soldiers. The governor of Bombay, Mountstuart Elphinstone, referred to the sepoy army as “a delicate and dangerous machine, which a little mismanagement may easily turn against us.” (Keene, 96).

The Battle of Plassey (1757)

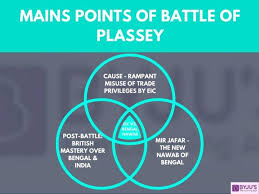

The British took advantage of the instability and the resulting regional tensions that occurred after the fall of the Mughal Empire (Blackwell, 35). Through machinations and intrigues, a force of eight hundred Europeans and 2,200 Indian troops defeated an army of 50,000 belonging to the ruler of Bengal (Blackwell, 35). This event is known as the “Battle of Plassey” that took place in 23 June 1757 under the leadership of Robert Clive, the EIC’s governor (the battle was held by the army of EIC). Many historians argue that the Indian defeat was due to a conspiracy of Mir Jafar with Clive against Siraj-ud-Daula, the nawab of Bengal. The largest contingent of the nawabi army remained inactive under Mir Jafar’s command. Jafar became the new nawab and served as “the puppet in the hands of the English” (Bandyopadhyay, 44). The nawab of Bengal was defeated along with his French allies that were in constant rivalry with the British. Thus, two powerful opponents were swiped away, marking the first steps towards Empire.

The power of the Company did not go unnoticed by British government. The Regulating Act of 1793 was the first one in a series of acts reining in the Company through parliamentary supervision. Arthur Wellesley, as governor-in-general (1797-1805), exercised his intention to make the Company the paramount power in India. He was able to suppress the little remaining French influence and also removed powerful Indian forces in both the north and the south. The British (at this period meaning the Company) were very powerful and they developed a bureucratuc infrastructure, “employing cooperating Indians, who came to constitute a new, urban class” (Blackwell, 35). The title of Governor-General had been bestowed upon the governor of the Bengal presidency (Calcutta), who had been granted power and rank over the governors of the Bombay and Madras presidencies. This was an administrative step toward unity which certainly aided the arrangement for empire. With the transition of the Company to the role of ruler, the British attitude toward Indians degenerated (Blackwell, 35).

Racism and Rebellion (The Sepoy Mutiny 1857)

Biased concepts regarding non-Western cultures and non-white peoples, arising from so-called social Darwinism and evangelicalism, provided rationale for imperial rule. Racism is a core characteristic of the British Empire in India. “By the late 18th century it had become commonplace among the British, irrespective of class, to despise Indians.” (Hiro, 277). There were many pockets of discontent among Indian people. Many believed that in addition to controlling their land, the British were trying to convert them to Christianity. The Indian people also resented the constant racism that the British expressed toward them (the age of imperialism, 359). As a reaction to these realities, Indian people decided to revolt against the EIC and its policy in India. This rebellion was termed the “Sepoy Mutiny of 1857”.

The causes were numerous, and included forcing the use of Western technologies—the railroad and telegraph—upon a highly traditional society, imposition of English as the language for courts and government schools, opening the country to missionaries (with the resulting fear of forced conversions), Company takeover of subsidiary states when a prince died without direct heir, increasing haughtiness and distance on the part of the rulers, and policies beneficial to the Company's profits, but even inimical to the people, and so on. The spark was the introduction of the Enfield rifle to the sepoy ranks, which necessitated handling of cartridges packed in beef and pork fat that sepoys had to bite. Both Muslims and Hindus were outraged and considered the act as an attempt to Christianize them (Blackwell, 36). The rebellion and the gruesome reaction to it were atrocious enough, but, as Maria Misra has observed, “The after-shock of the Rebellion was if anything even more influential than the event itself” (Misra, 7).

The East India Company took more than a year to regain control of the country. The British government sent troops to help them. The Indians could not unite against the British due to weak leadership and serious splits between Hindus and Muslims. Hindus did not want the Muslim Mughal Empire restored. Indeed, many Hindus preferred British rule to Muslim rule. Most of the princes and maharajahs who had made alliances with the East India Company did not take part in the rebellion. The Sikhs, a religious group that had been hostile to the Mughals, also remained loyal to the British. Indeed, from then on, the bearded and turbaned Sikhs became the mainstay of Britain’s army in India (the Age of Imperialism, 360). A curtain had fallen, and the two sides would never trust each other again.

The Official Declaration of the British Indian Empire

The Crown took over direct responsibility and the East India Company was disbanded (Maddison, 2005). In 1877, Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India. Governor-Generals, popularly referred to as Viceroys (after 1858), came and went, but the direction remained clear: “Imperial rule for the profit of Britain, not for the welfare of the people of India” (Blackwell, 36). To reward the many princes who had remained loyal to Britain, the British promised to respect all treaties the East India Company had made with them. They also promised that the Indian states that were still free would remain independent. Unofficially, however, Britain won greater and greater control of those states. The Sepoy Mutiny fueled the racist attitudes of the British. The British attitude is illustrated in a quote by Lord Kitchener, British commander in chief of the army in India who said that “It is this consciousness of the inherent superiority of the European which has won for us India. However well-educated and clever a native may be, and however brave he may prove himself, I believe that no rank we can bestow on him would cause him to be considered an equal of the British officer” (qtd. in. Sammis, 83).

The methods and Impact of British Imperialism and colonialism in India

Divide and Rule: The British used the strategy of “divide and rule” to provoke hostility between Hindus and Muslims. The divide and rule policy used religion to drive a wedge between Indians which eventually resulted in the death and displacement of millions of people, as well as the destruction of key economic assets (Lyer, 2010; Tharoor, 2017). The British realized that India was a land of sociocultural diversity, and to exploit and control the lands, it was imperative to incite Hindus against Muslims and the masses against the princes (Baber, 1996, p. 127). In the 1857 mutiny, Hindu and Muslim soldiers were unified around loyalty to the Mughal prince, which worried the British rulers who devised policies and programs to fracture relationships between Muslims and Hindus. For example, the British ousted Muslims from power and they naturally were hostile to the British who favored Hindus (Rahman, Ali, and Khan, 4).

Spreading colonial education: Prior to the British arrival, Muslim children were schooled in madrasas and maktabs, and Hindu children were taught in pathshalas and tols. These institutions taught children Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, theology, grammar, logic, law, mathematics, metaphysics, medicine, and astrology (Chopra, Puri, & Das, 2003; Nurullah & Naik, 1943). The British government, however, ignored this faith-based education system and replaced it with a British system. Thomas Babington Macaulay, a British, made a comment that reflects the British intentions for introducing English education for Indians:

We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. To that class, we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees’ fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population. (Macaulay, 1965, p. 116)

The British did not save any effort to change every bit of Indian culture. They interfered in every single cultural tradition, including religious matters, and attempted to change the beliefs that had ruled the lives of both Muslims and Hindus. This includes specific cultural practices of Indian women as well. They used the argument of the white man’s burden in these missions of changing Indian culture.

The application of British law systems: the codified English law administered by the courts was initially applied only to Europeans residing in the sub-continent. However, by 1773 it was proposed that in matters of marriage, inheritance, and other individual affairs, Islamic laws should be applied to Muslims, and Hindu laws to Hindus (Otter, 2012). While it is not clear whether this bifurcation of the law was proposed to introduce the policy of divide and rule, it had long lasting impacts that ultimately led to the division of the sub-continent based on religion. This idealization of Indigenous Indian customs and laws was, however, short lived. For instance, the British philosopher James Mill considered Indigenous Indian laws to be “a disorderly compilation of loose, vague, stupid, or unintelligible quotations and maxims selected arbitrarily from book of law, book of devotion, and books of poetry; attended with a commentary which only adds to the absurdity and darkness; a farrago by which nothing is defined, nothing established” (Judd, 2004, p. 38).

Weakening India’s local Industry: Several Indian authors have argued that British rule led to a de-industrialization of India. R.C. Dutt argued:

India in the eighteenth century was a great manufacturing as well as a great agricultural country, and the products of the Indian loom supplied the markets of Asia and Europe. It is, unfortunately, true that the East India Company and the British Parliament, following the selfish commercial policy of a hundred years ago, discouraged Indian manufacturers in the early years of British rule in order to encourage the rising manufactures of England. Their fixed policy, pursued during the last decades of the eighteenth century and the first decades of the nineteenth, was to make India subservient to the industries of Great Britain, and to make the Indian people grow raw produce only, in order to supply material for the looms and manufactories of Great Britain”. (Dutt, xxv)

National beginnings

Surprisingly, the inception of the Indian National Congress (INC) and the first stirrings of a national movement owed its origins to a Briton. Allan Ovtavian Hume in an address to the graduating class of Calcutta University. The INC, composed of lawyers and other intellectuals met for the first time on December 28, 1885. Their primary objective was to give Indians a greater voice in their own destinies. Confrontation with the British arose soon after the establishment of the congress party (Welsh, 2011). This organization demanded that “the Government should be widened and that the people should have their proper and legitimate share in it”(qtd. in. Hiro, 259). It involved about seventy-two delegates, from various regions, and consisted mostly of upper class Hindus and Parsis (many of them lawyers) with only two Muslims in attendance. It was through this organization, under the leadership of lawyers such as Motilal Nehru and his son Jawaharlal Nehru (India's first prime minister), and M. K. Gandhi, that India achieved independence (Blackwell, 37).

Such a meeting, let alone the organization itself (or, for that matter, the nationalist/independence movement), would not have been possible had it not been for the English language as a lingua franca, which stemmed from the 1835 decision by the Governor-General to make English the official language of instruction. That decision opened a can of worms: men educated in English law saw the possibilities of constitutional democracy. No one Indian language could claim the majority of speakers, and English provided the bridge that made communication possible between the educated from different parts of India. The importance of this development cannot be overemphasized. Related developments included the establishment of universities (oddly, in 1857) in Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta; a vibrant (if often censored) press, and Indian literature in English. These all are evident and thriving yet today, and strongly so. The most important development might well have been that of nationalism, an attempt to override the British policy of divide-and-rule (which played on Hindu-Muslim antipathy). Of course, the creation of Pakistan showed that the dream was not completely successful—yet India today is a successful democracy. And the nationalist movement did bring the diverse cultures and languages, the religious sects and castes, into a new identity: Indian.

Terms explained

The Raj: It was Imperial Britain’s takeover of the rights and responsibilities of the former British East India Company, following the latter’s dissolution due to mismanagement.

Nawab: a deputy ruler or viceroy in India. In previous times it was bestowed by the reigning Mughal emperor to semi-autonomous Muslim rulers of subdivisions or princely states in the Indian subcontinent.

Governor-general: the representative of the monarch of the UK in India. After 1858 the governor-general was given the title of the “Viceroy”.

Sepoy: An Indian soldier serving under British or other Europian orders.

-

-